Beneath London’s streets lies an alternative map of the capital, and it’s one that doesn’t appear on your standard Tube guide. These are the ghost stations: abandoned, decommissioned, or repurposed London Underground stations that once thrived with commuters but now serve as time capsules of British history, architecture, and wartime resilience.

If you’re a London tourist, a history enthusiast, or just fascinated by what lies beneath the city, this deep dive into London’s disused tube stations will take you on a journey of lost platforms, hidden bunkers, wartime secrets, and unexpected second lives. From Aldwych to the long-lost British Museum station, this blog post explores the mystery and magic of London’s hidden Underground.

Aldwych Station: From Ghost Stop to Movie Star

Located on the Strand in Westminster and once part of the Piccadilly line, Aldwych Station (formerly Strand Station) opened in 1907. Designed by the iconic Leslie Green, known for his signature oxblood red terracotta facades, Aldwych followed the Arts and Crafts architectural tradition. Even today, the green and cream tiles remain intact, preserving its Edwardian charm.

Though aesthetically stunning, Aldwych never attracted the commuter numbers it needed. Built with two platforms, only one was regularly used, and plans to extend the line to Waterloo or the City never materialized. The station closed in 1994 due to high maintenance costs and low usage, often 450 passengers a day.But the story didn’t end there. During World War II, Aldwych became a bomb shelter and storage site for the British Museum’s priceless Elgin Marbles. Today, it’s a training ground for emergency services and a favourite filming location, appearing in ‘V for Vendetta’, ‘Atonement’, ‘Sherlock’, and more. You can even book a tour through the London Transport Museum.

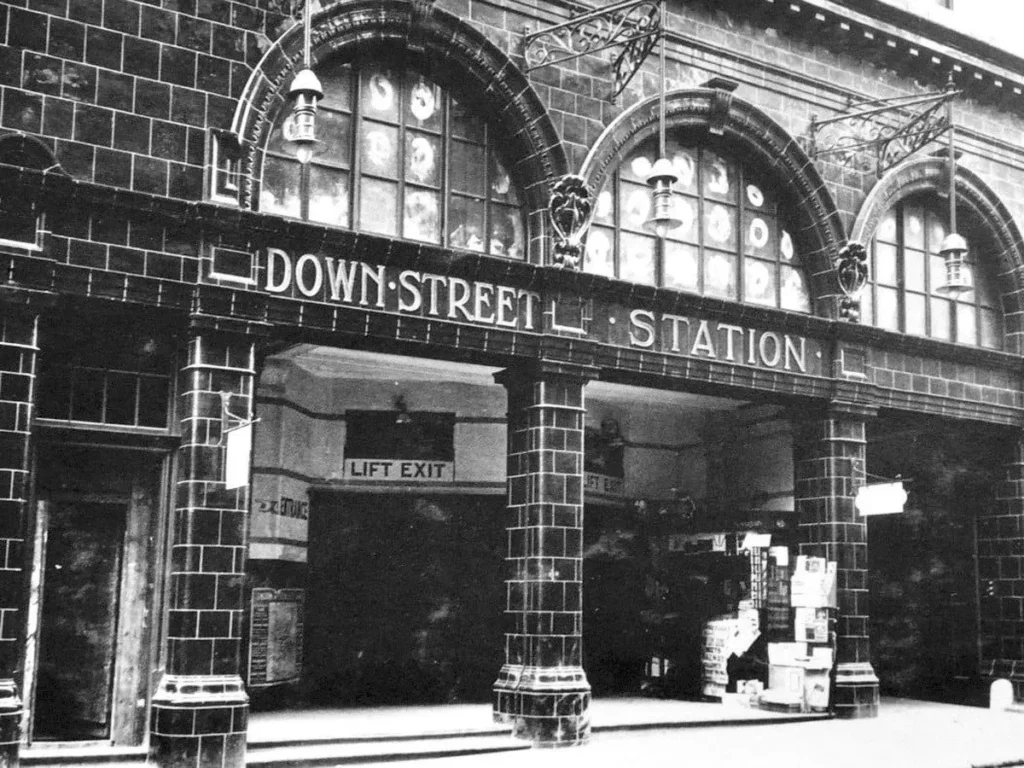

Down Street: Churchill’s Secret Bunker

Tucked away in Mayfair, Down Street Station opened in 1907 and closed in 1932 due to low passenger numbers. Its location between Hyde Park Corner and Green Park (formerly Dover Street) made it redundant from the start. Wealthy residents preferred taxis to tube rides.

But during World War II, Down Street was reborn as a bomb-proof bunker for the Railway Executive Committee, which oversaw Britain’s rail operations. The transformation included sealed tunnels, blast-proof doors, and even a private lift. Winston Churchill himself used the station as a secure meeting site. Known only to insiders as “The Barn,” it featured gourmet meals and was considered one of the safest places in London.

Today, the station still supports London Underground operations but remains closed to the public. However, plans to repurpose it for commercial use are under discussion, giving it yet another potential chapter.

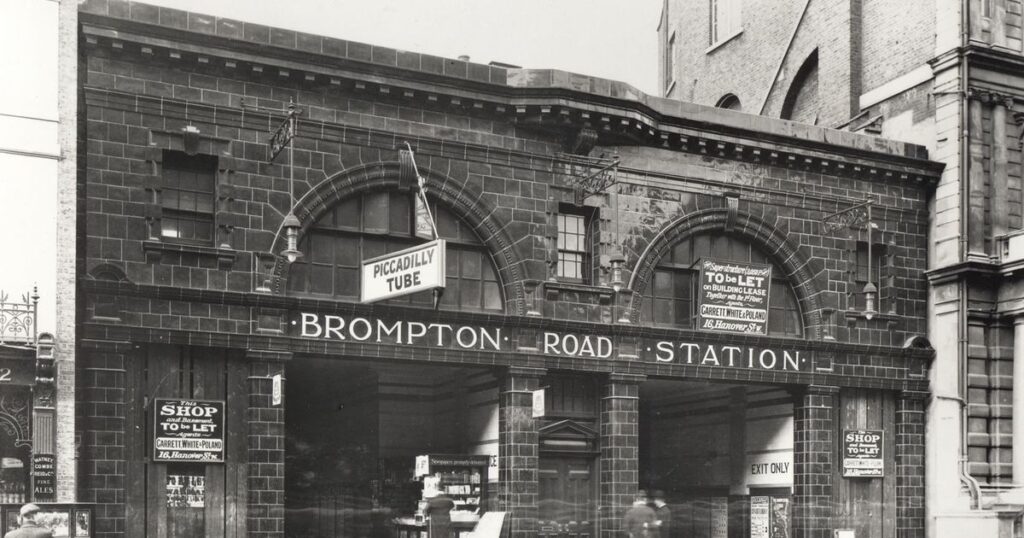

Brompton Road: From Quiet Platform to Anti-Aircraft HQ

Opened in 1906 and closed in 1934, Brompton Road Station was another Leslie Green creation located between South Kensington and Knightsbridge. Despite its central location in affluent Knightsbridge, it suffered from low footfall.

But in wartime, it became a key asset. Bought by the War Office in 1938 for £22,000 (about £1.7 million today), the station was converted into the HQ for the 26th (London) Anti-Aircraft Brigade. It coordinated London’s air defences and was even visited by Churchill. There’s even a rumor that Rudolf Hess was interrogated there after crash-landing in Scotland.

In 2014, the Ministry of Defence sold the station to a Ukrainian businessman with alleged Kremlin ties for £53 million. Plans to turn it into luxury flats remain unclear. For now, Brompton Road remains a silent witness to a dramatic past.

York Road: The Forgotten Gateway to King’s Cross

York Road Station opened in 1906 and closed in 1932. Located between King’s Cross and Caledonian Road on the Piccadilly line, it suffered due to its industrial surroundings and close proximity to major stations.

Though its surface buildings still stand and have housed businesses like the Victor Printing Company, the station has not seen passengers in nearly a century. Multiple proposals have been floated reopening York Road, particularly during the King’s Cross regeneration. But the estimated £21 million renovation cost has kept it shuttered.However, you can still see York Road station in all its glory by visiting the London Transport Museum and for a virtual tour of the station.

South Kentish Town: 17 Years of Service, a Century of Legacy

Originally planned as “Castle Road,” South Kentish Town Station opened in 1907 and closed in 1924 after a temporary closure during a power station strike became permanent due to low usage. Like its peers, it found new life during WWII as an air raid shelter.Today, the station building is home to “Mission Breakout,” a historical escape room experience that lets you interact with the station’s heritage. While it never fulfilled its original transport purpose, South Kentish Town remains a quirky footnote in Camden’s colourful l history.

British Museum Station: The Lost Link to London’s Treasures

Opened in 1900 by the Central London Railway (now the Central Line), British Museum Station was strategically located on High Holborn. But when Holborn Station opened in 1906 less than 100 yards away, it sealed British Museum Station’s fate. Without an interchange and facing declining use, it closed in 1933.

During WWII, it played a behind-the-scenes role in civil defence, serving as a control centre re for emergency operations. The station building was demolished in 1989, and the site is now occupied by a branch of Nationwide. Still, some tunnels remain in use for maintenance purposes.

Oh, and let’s not forget the ghost stories. Legend has it that the spirit of an Egyptian princess named Amen-Ra ( Also known as the Unlucky Mummy) haunts the site, wandering the Underground in search of her missing mummy. Some say her screams echo through nearby Covent Garden and Holborn stations.

Why These Stations Matter Today

London’s disused Underground stations are more than just relics. They reflect the city’s evolving transport needs, architectural trends, and wartime adaptability. They tell stories of ambition, failure, resilience, and reinvention.

For visitors interested in British history or hidden London, these stations offer a rare glimpse into the unseen layers of the city. They also provide compelling backdrops for films, training exercises, and urban exploration.

So next time you’re riding the Tube or walking the streets of London, look a little closer. That abandoned building you pass by might be a doorway into one of the city’s most fascinating stories.